परिचय

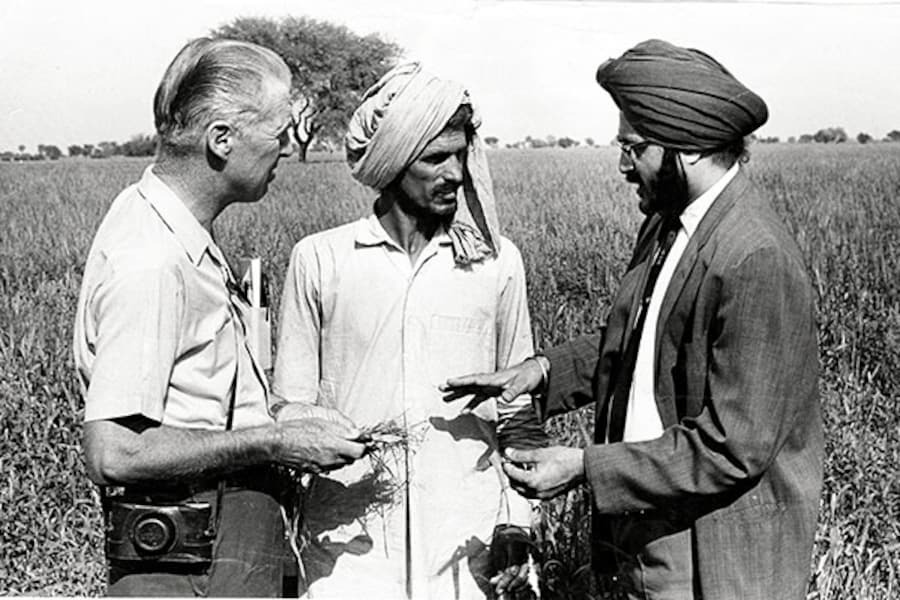

The Green Revolution in India refers to the rapid adoption of high‑yielding varieties (HYV) of wheat and rice, alongside expanded irrigation, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, credit, and procurement support that transformed foodgrain production beginning in the mid‑1960s, with breakthrough seasons from 1966 onward in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh. Spearheaded nationally by M.S. Swaminathan in collaboration with Norman Borlaug and supported by policy measures under ministers such as C. Subramaniam, the program lifted yields, ended chronic grain dependence, and set India on the path to food self‑sufficiency by the early 1970s.

Background: Food crisis to technological change

- Pre‑1965 pressures: Droughts in 1965–67, stagnant yields, and heavy reliance on PL‑480 grain imports created a crisis that pushed policy toward technology‑led growth and assured state support for inputs and procurement.

- Scientific collaboration: Indian researchers (IARI and partners) tested and multiplied semi‑dwarf Mexican wheat (e.g., Sonora‑64, Lerma Rojo) and prepared for rapid dissemination; a large 1965 seed consignment arrived amid war‑time delays and was sown for 1966 campaigns.

- Strategic geography: Punjab was chosen for initial scaling due to reliable canal and tube‑well irrigation, fertile alluvial soils, and a strong farm base; Haryana and western UP followed closely.

What changed: Seeds, water, inputs, and markets

- HYV seeds: Semi‑dwarf wheat and later IRRI rice (IR8 “miracle rice,” released in late 1966) that could absorb higher fertilizer doses without lodging drove the yield jump.

- Irrigation and inputs: Expansion of canals/tube‑wells, nitrogen‑phosphorus fertilizers, and modern plant protection formed the standard “package of practices” adopted in the northwest plains.

- Price and procurement: Government assured minimum prices and procurement with public distribution, catalyzing rapid farmer uptake of wheat HYVs from rabi 1966–67 onward.

Timeline and early breakthroughs (1965–1971)

- 1965: Large shipments of Mexican wheat seed dispatched; national demonstrations and multi‑location trials validate high response to inputs.

- Late 1966: IRRI releases IR8 rice; adoption across Asia begins, with India part of the early wave of trials and multiplication.

- 1966–68: Wheat HYVs rapidly spread across Punjab–Haryana; India’s wheat output accelerates sharply from the 1965 base.

- 1971: India attains foodgrain self‑sufficiency, a symbolic turning point after decades of shortages.

Production gains: Wheat first, rice follows

- Wheat: India’s wheat production rose from about 12 million tons in 1965 to about 20 million tons by 1970, reflecting concentrated HYV adoption in irrigated northwest zones. Punjab’s wheat output soared as semi‑dwarf cultivars met reliable water and fertilizer—documented by sustained yield growth through the 1970s and 1980s.

- Rice: IR8 (1966) and successors like IR36, combined with irrigated expansion and input use, raised rice yields substantially; India became a successful rice producer and later a major exporter, with IR8’s 5–10 t/ha potential under good management widely cited from early trials.

Key figures and institutions

- M.S. Swaminathan: Widely recognized as the “Father of the Green Revolution in India” for leading the scientific and institutional push to adapt and disseminate HYVs.

- Norman Borlaug: Brought Mexican semi‑dwarf wheat to India and worked with Indian scientists to accelerate seed supply and agronomy.

- C. Subramaniam: Food and Agriculture Minister credited as the “political father” for policy backing of inputs, prices, and procurement that enabled farmer adoption.

- IARI/ICAR and IRRI/CIMMYT: National and international research partners that provided varieties, breeding pipelines, and agronomic know‑how.

Policy architecture that enabled scale

- Input access: Subsidized/imported fertilizers, seed multiplication, and credit networks underpinned rapid intensification.

- Assured markets: Minimum support prices and procurement via FCI and state agencies reduced market risk and encouraged acreage shifts toward wheat and later irrigated rice.

- Irrigation push: Public canals and private tube‑wells expanded in Green Revolution states, making HYV packages viable and reliable.

Regional focus and diffusion

- Core belt: Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh achieved the earliest and largest productivity gains due to irrigation and land characteristics favorable to intensive wheat–rice rotations.

- Wider adoption: Subsequent diffusion extended to parts of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and eastern India as irrigation and extension improved, with rice HYVs spreading through irrigated and favorable rainfed ecologies.

Impacts: Food security, prices, and growth

- Food self‑sufficiency: By 1971, India met domestic cereal demand, dramatically reducing vulnerability to imports and food aid; by the late 1970s it emerged among the world’s larger agricultural producers.

- Price and availability: Higher output eased shortages and lowered real prices for staple grains over time, especially with rising rice supplies from HYVs and expanded irrigated area.

- Rural transformation: The wheat–rice system increased marketed surplus, stimulated mechanization and services, and reoriented cropping patterns toward input‑responsive cereals in the northwest plains.

Costs and criticisms (early signals)

- Input dependence: Semi‑dwarfs were highly responsive to chemical fertilizers, increasing import bills and subsidy burdens as adoption widened.

- Cropping shifts: Gains were concentrated in wheat and irrigated rice; pulses, millets, and coarse cereals often lost area or policy attention, with nutritional and diversity implications.

- Environmental stresses: Over‑extraction of groundwater, soil nutrient imbalances, and pesticide externalities were flagged increasingly in Punjab–Haryana systems as intensification matured.

Key dates and facts

- August–October 1965: Major Mexican wheat seed consignments shipped and received; scaling campaigns prepared for 1966 sowing.

- Late 1966: IR8 rice released by IRRI; early Indian trials showcase its high yield potential under good management.

- 1965–1970: India’s wheat output jumps from ~12 to ~20 million tons as HYVs spread across irrigated northwest states.

- 1971: India becomes self‑sufficient in food production, marking the Green Revolution’s strategic success.

Interesting facts

- “Miracle rice” IR8, released in 1966, delivered unprecedented yields in well‑managed Asian trials, catalyzing a parallel rice revolution that complemented India’s initial wheat surge.

- Punjab’s rice output—historically minor—expanded dramatically under Green Revolution practices, rising from a fraction of a million tons mid‑century to several million tons by the 1980s as wheat–rice rotations took hold.

- The early wheat breakthrough hinged not just on seeds but on state guarantees—procurement and prices—that made input‑intensive cultivation a lower‑risk bet for farmers.

Legacy and significance

The 1966 Green Revolution inflection in India fused science, infrastructure, and state policy to end recurrent grain crises, rapidly raising yields in irrigated zones and achieving foodgrain self‑sufficiency within a few years. It also set the template—both promise and warnings—for subsequent phases of agricultural development: the power of research‑led intensification under supportive markets and water, and the long‑run need to manage resource stress, diversify diets, and sustain productivity gains beyond a narrow wheat–rice focus.

इस बारे में प्रतिक्रिया दें