The Khajuraho Group of Monuments ( Khajuraho Temples) is a UNESCO World Heritage site and a masterpiece of the Nagara style of architecture, built by the Chandela Dynasty between 950 and 1050 CE in central India. Often misunderstood for their famous erotic sculptures, these intricate carvings actually represent only 10% of the art, with the vast majority depicting war, daily life, and spiritual devotion. Originally a complex of 85 temples, the 23 surviving structures stand as soaring metaphors for the Himalayan peaks (Mount Meru), guiding devotees from the worldly desires of the outer walls to the spiritual silence of the inner sanctum.| Feature | Details |

| Location | Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| Built By | Chandela Dynasty (950 CE – 1050 CE) |

| Architecture Style | Nagara Style (North Indian) |

| Key Temples | Kandariya Mahadeva, Lakshmana, Chaunsath Yogini |

| UNESCO Status | Inscribed in 1986 |

| Best Time to Visit | October to March (Dance Festival in Feb) |

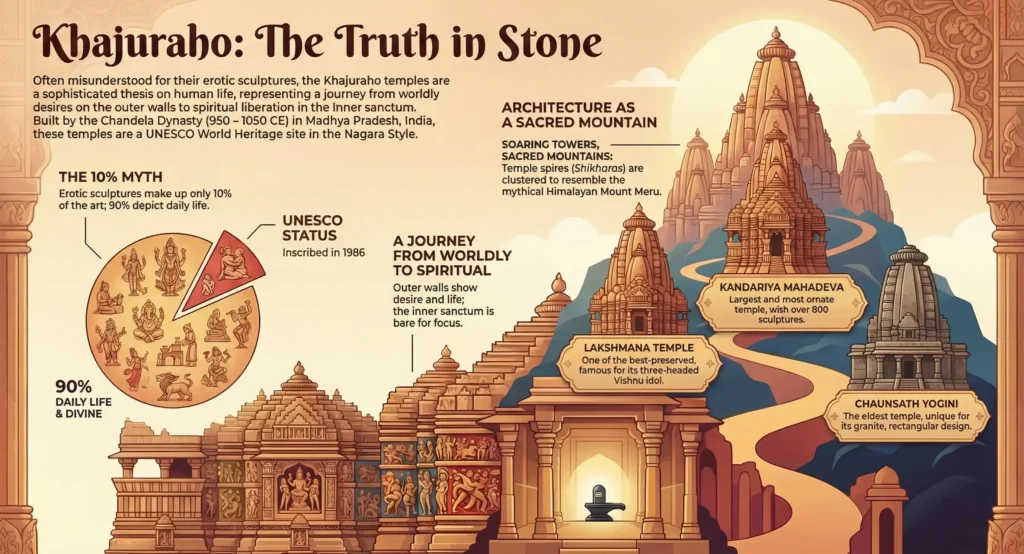

The Khajuraho Group of Monuments is perhaps the most misunderstood architectural marvel in India. Often reduced to “the Kamasutra temples” by casual tourists, these sandstone structures are actually a sophisticated thesis on human life, etched in stone.

Built by the warrior-kings of the Chandela dynasty over a 100-year burst of creativity (950–1050 CE), Khajuraho represents the zenith of Nagara architecture. Here, the stone doesn’t just stand; it breathes, dances, and teaches.

But why did a dynasty build temples covered in desire? And what do they really mean?

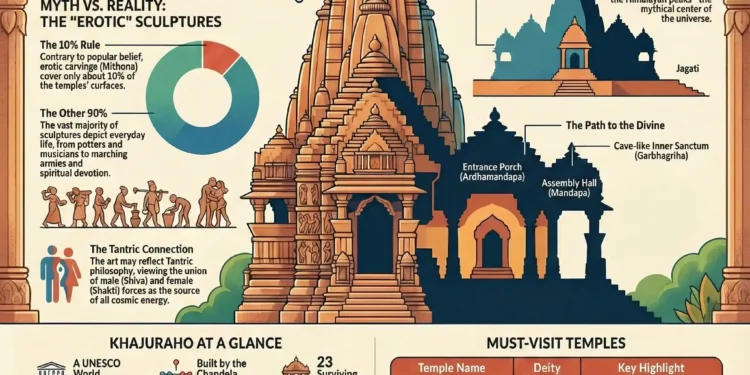

1. Myth vs. Reality: The “Erotic” Sculptures

The most common question about Khajuraho is: Why are there erotic carvings on a holy temple? To understand this, we must look past modern morality and into ancient philosophy.

- The 10% Rule: Contrary to popular belief, erotic scenes (Mithuna) make up only about 10% of the total wall space. The other 90% depict everyday life: potters, musicians, women applying kohl, and armies marching.

- The “Outer” World: In Hindu philosophy, the temple represents the universe. The outer walls depict the physical world—desire (Kama), war, and daily life. As you move inside the temple towards the sanctum (Garbhagriha), the carvings stop. This symbolizes leaving worldly desires behind to enter a state of pure spiritual focus.

- The Tantric Connection: Many historians believe the Chandelas were influenced by Tantric traditions, which view the union of male and female forces (Shiva and Shakti) as the source of all cosmic energy.

2. Architecture: A Mountain of Stone

The Khajuraho temples follow the Nagara style of Northern India, but with a unique twist.

Instead of being enclosed within walls, each temple stands on a high platform (Jagati), lifting it above the common ground. The main tower (Shikhara) is surrounded by smaller subsidiary towers (Urushringas). When viewed from a distance, this creates the visual effect of a mountain range, symbolizing Mount Meru, the mythical center of the universe.

Key Architectural Elements:

- Ardhamandapa: The entrance porch.

- Mandapa: The assembly hall where devotees gathered.

- Garbhagriha: The dark, cave-like inner sanctum housing the main deity.

- Pradakshina Patha: The circumambulatory pathway for ritual walking around the deity.

3. The Must-Visit Temples

Of the surviving 23 temples, they are divided into three groups: Western, Eastern, and Southern. If you are short on time, focus on the Western Group.

| Temple Name | Deity | Key Highlight |

| Kandariya Mahadeva | Shiva | The largest and most ornate temple; resembles a mountain peak. Contains over 800 sculptures. |

| Lakshmana Temple | Vishnu | One of the oldest and best-preserved. Famous for its three-headed idol of Vishnu (Vaikuntha). |

| Chaunsath Yogini | Kali | The oldest temple (900 CE), made of granite instead of sandstone. It is the only rectangular temple here. |

| Parsvanatha | Jain Tirthankaras | Located in the Eastern Group, this Jain temple is famous for its intricate “magic square” mathematical inscriptions. |

4. Practical Travel Guide

Best Time to Visit: The ideal time is October to March.

- Winter (Nov-Feb): Perfect weather for walking. The famous Khajuraho Dance Festival takes place in February, where classical dancers perform against the backdrop of the lit-up temples.

- Summer (April-June): Avoid. Temperatures can hit 45°C (113°F).

How to Reach:

- By Air: Khajuraho has its own airport (HJR) with connections to Delhi and Varanasi.

- By Train: The Khajuraho Railway Station connects to Delhi (via the Uttar Sampark Kranti Express).

Khajuraho represents the zenith of building up towards the heavens; to see where it all began with artisans digging in to the mountains, read our feature on Ajanta, Ellora, and the Secrets of Rock-Cut Architecture

Conclusion: A Timeless Mirror

The Khajuraho temples are not merely stone monuments; they are a philosophical journey carved into the landscape of India. They challenge the viewer to look beyond the surface—beyond the eroticism and the grandeur—to find the balance between the physical and the spiritual. While the Chandela kings have long vanished, their message remains etched in sandstone: that human life is a celebration of Dharma (duty), Artha (prosperity), Kama (pleasure), and ultimately, Moksha (liberation) . To visit Khajuraho is to walk through a library of human experience, where every pillar has a story and every face has a soul.

Now that you have explored the soaring heights of Khajuraho’s structural temples, dive deep into the earth to discover the subtractive engineering secrets in our guide to Indian Rock-Cut Architecture

If you think you have rememberd everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. According to the text, what is the primary symbolic function of the temple’s outer walls, which feature carvings of daily life, war, and desire?

#2. The architectural design of the Khajuraho temples, with a main tower surrounded by smaller ones, is intended to visually evoke what natural or mythical feature?

#3. Which Khajuraho temple is noted for being the oldest, built from granite instead of sandstone, and having a unique rectangular layout?

#4. What common misconception about the Khajuraho temples does the ‘10% Rule’ mentioned in the text address?

#5. The architectural style of the Khajuraho temples, characterized by its soaring towers (Shikharas) and high platforms (Jagati), is known as what?

#6. The Kandariya Mahadeva temple is considered the largest and most ornate temple at Khajuraho. To which deity is it dedicated?

#7. What is the name of the dark, cave-like inner sanctum of a Khajuraho temple that houses the main deity?

#8. Besides the pleasant weather, what major cultural event makes February a particularly good time to visit Khajuraho?

FAQ

Why are there erotic sculptures on Khajuraho temples?

They represent Kama (desire) as one of the four goals of life in Hinduism, alongside Dharma, Artha, and Moksha. They also symbolize the “outer world” of illusion (Maya) that one must leave behind before entering the inner sanctum.

Who built the Khajuraho temples?

They were built by the rulers of the Chandela Dynasty between 950 and 1050 CE.

How many temples are there in Khajuraho?

Originally, there were 85 temples. Today, only roughly 23 to 25 temples have survived natural elements and destruction.

Is Khajuraho a UNESCO World Heritage site?

Yes, the Khajuraho Group of Monuments was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986 for its outstanding architectural and artistic value.